I'm not going to pussyfoot around here and will just get straight to the point: I hate The Left Hand of Darkness. I was completely into the idea behind the book, and Ursula K. Le Guin is a fine writer who is smart as a whip; she wrote one of my favorite books ever, The Lathe of Heaven. I actually had high expectations for this book considering I've had good experience with Le Guin before and since this was considered an all-time classic. Unfortunately, the book fell virtually to the opposite of my expectations.

First and foremost, the central idea behind the book is that of a species which has an inherent ability of changing their biological sex. This is a great idea of which much insight could be derived, especially in this current time when transsexual rights are currently disputed (and the book was written in 1969, so much like a great number of science fiction it was, in a way, ahead of its time). Unfortunately, Le Guin barely touches on the subject at all, and doesn't do so in any meaningful way, shape, or form.

What Le Guin does instead is plenty of world, scene, and mythology-building. This may not sound bad to all readers of this blog, and actually may excite some, but I will explain why this makes the novel a major pain to read with a comparison. Those who have read Mary Shelley's Frankenstein may remember the scene in which Victor Frankenstein treks through a mountain range, which is supposed to be symbolic of Victor's feelings and what he is going through (not in a literal sense, more in terms of how the story is shaping up). That scene wasn't the greatest in the book because it's a bit of a chore to get through mundane details of his travels, but it does at least serve a purpose and I certainly don't mind that kind of symbolic showcasing.

But imagine that one scene is stretched to three hundred pages long. It was for that reason I, frankly, could not finish this book; I tread most of the way through, but I stopped because whenever I'd read it I'd become tired and on more than one occasion even fell asleep, and on one occasion in particular was even after drinking caffeine. I then read a detailed synopsis and was glad afterward that I stopped, because it was clear at that point, Le Guin wasn't doing anything of importance with her otherwise interesting idea and was ultimately utilizing the characters and plot to serve the scene rather than the other way around. You can, like with Frankenstein, do that to a point, but writing an entire book this way makes for a tiresome and irritating experience.

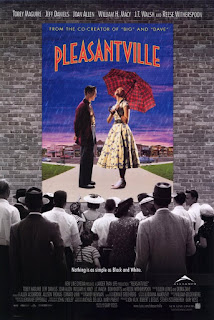

What little story exists is simply a political struggle wrapped around what honestly feels like a fantasy tome. I realize the book is supposed to be science fiction, and overall I wouldn't say it isn't, but it barely feels like science fiction at all. In fact, the covers of the novel, except maybe two editions (including the picture I used above, which I thought was the most interesting cover and that says a lot), just tend to slap ice on the cover and boom, published. Even if the back covers and such proudly proclaim the novel as science fiction, they still go out of their way to otherwise dress the novel as not such at all, and after reading, I can see why, because it barely feels like science fiction at all. I get the frozen tundras are important to the novel, but I can see that enough in the writing.

But I digress. This is, unfortunately, yet another "classic" I can't help but find heavily overrated. I don't have a clue as to why this novel is so popular; I understand that, at the time this was written, this idea of Le Guin's was considered fresh and possibly even taboo, but a fresh idea does not a good book make. The idea was used, quite lightly, as dressing for the book. I don't know about anybody else, but I like to drench my lettuce in ranch rather than use a tiny squirt. No new insight was truly gained out of this idea after having read this book/synopsis, and I know that's completely possible. That's one of the main reasons I love science fiction is because I love the ideas and how they can be treated to teach us about ourselves, where we're headed, how we're heading there, etc. So I consider this book a failure, on almost every level besides the technical writing prowess Le Guin clearly possesses. Otherwise, I see it as a waste of time, since Le Guin has written better anyway. One of the biggest disappointments yet.

First and foremost, the central idea behind the book is that of a species which has an inherent ability of changing their biological sex. This is a great idea of which much insight could be derived, especially in this current time when transsexual rights are currently disputed (and the book was written in 1969, so much like a great number of science fiction it was, in a way, ahead of its time). Unfortunately, Le Guin barely touches on the subject at all, and doesn't do so in any meaningful way, shape, or form.

What Le Guin does instead is plenty of world, scene, and mythology-building. This may not sound bad to all readers of this blog, and actually may excite some, but I will explain why this makes the novel a major pain to read with a comparison. Those who have read Mary Shelley's Frankenstein may remember the scene in which Victor Frankenstein treks through a mountain range, which is supposed to be symbolic of Victor's feelings and what he is going through (not in a literal sense, more in terms of how the story is shaping up). That scene wasn't the greatest in the book because it's a bit of a chore to get through mundane details of his travels, but it does at least serve a purpose and I certainly don't mind that kind of symbolic showcasing.

But imagine that one scene is stretched to three hundred pages long. It was for that reason I, frankly, could not finish this book; I tread most of the way through, but I stopped because whenever I'd read it I'd become tired and on more than one occasion even fell asleep, and on one occasion in particular was even after drinking caffeine. I then read a detailed synopsis and was glad afterward that I stopped, because it was clear at that point, Le Guin wasn't doing anything of importance with her otherwise interesting idea and was ultimately utilizing the characters and plot to serve the scene rather than the other way around. You can, like with Frankenstein, do that to a point, but writing an entire book this way makes for a tiresome and irritating experience.

What little story exists is simply a political struggle wrapped around what honestly feels like a fantasy tome. I realize the book is supposed to be science fiction, and overall I wouldn't say it isn't, but it barely feels like science fiction at all. In fact, the covers of the novel, except maybe two editions (including the picture I used above, which I thought was the most interesting cover and that says a lot), just tend to slap ice on the cover and boom, published. Even if the back covers and such proudly proclaim the novel as science fiction, they still go out of their way to otherwise dress the novel as not such at all, and after reading, I can see why, because it barely feels like science fiction at all. I get the frozen tundras are important to the novel, but I can see that enough in the writing.

But I digress. This is, unfortunately, yet another "classic" I can't help but find heavily overrated. I don't have a clue as to why this novel is so popular; I understand that, at the time this was written, this idea of Le Guin's was considered fresh and possibly even taboo, but a fresh idea does not a good book make. The idea was used, quite lightly, as dressing for the book. I don't know about anybody else, but I like to drench my lettuce in ranch rather than use a tiny squirt. No new insight was truly gained out of this idea after having read this book/synopsis, and I know that's completely possible. That's one of the main reasons I love science fiction is because I love the ideas and how they can be treated to teach us about ourselves, where we're headed, how we're heading there, etc. So I consider this book a failure, on almost every level besides the technical writing prowess Le Guin clearly possesses. Otherwise, I see it as a waste of time, since Le Guin has written better anyway. One of the biggest disappointments yet.