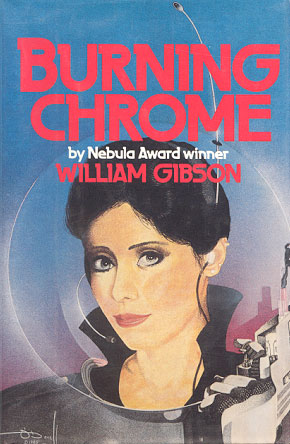

In what I'm sure will become an infamous review of mine, my review of Neuromancer was scathing of not only the novel, but of William Gibson as well. I figured his style was great, but I couldn't understand what was going on, as if the narrator he utilized in his story was a drunk telling some randomly garbled story. I figured, after seeing I had a couple of short stories of his, “You know what, his style might better suit him for the short form.”

Boy was I

dead on with that prediction.

As much as

I trashed Gibson before, I must admit, the short story seems to truly be his

forte. It is in this form that he can sometimes confuse readers and introduce

odd concepts and not be entirely straightforward and still manage to be

coherent and perfectly enthralling. I will admit one flaw that Neuromancer

had as well, which was sheer predictability, but I'd otherwise recommend

“Burning Chrome”, set in the same universe, far more. Every single problem I

had with Neuromancer was not a problem at all here.

For

starters, similar terms are used here within this story, and one, ice, is even

described to some degree, enough for most to understand, and much like Neuromancer,

it's creative in its descriptions of surroundings (this case being better,

obviously). Beyond that, there is no real break up in the scenes that would

entail missing anything important. That was the biggest problem Neuromancer

had, and it seems to be thanks in part to a greater-utilized narrator, one who

seems sobered, intelligent, and ultimately human. In fact, all of the

characters were people I could care about, even the people who are kind of

jerks. The narrator actually cares about and describes in great fashion the

other characters and how he feels about them. That is exactly the kind of

person I want to read about, and I didn't get that in Neuromancer.

Which

brings me to my most pressing question: What happened to you, Gibson? What

changed in you from the time you wrote this excellent short story to writing Neuromancer?

It was, after all, a short couple of years. Were you stressed by time

constraints? Was the novel truly unfinished? Seems like it was, despite the

excellent writing otherwise. Or did you really think the story was great as it

was? If not, did the editor think otherwise? Somehow, that seems to be the case

with the general audience, who seem to be overlooking this wonderful gem for

that. That, to me, is a shame.

For

everyone else who dislikes Neuromancer like I do (as if I haven't said

it enough), I still strongly recommend “Burning Chrome” to you. I seriously

doubt you'll be disappointed with this one.

Additional Super Fun Fact: Chromium is a chemical element which has a high rate of corrosion resistance and is quite hard. Keep this in mind while reading the story.